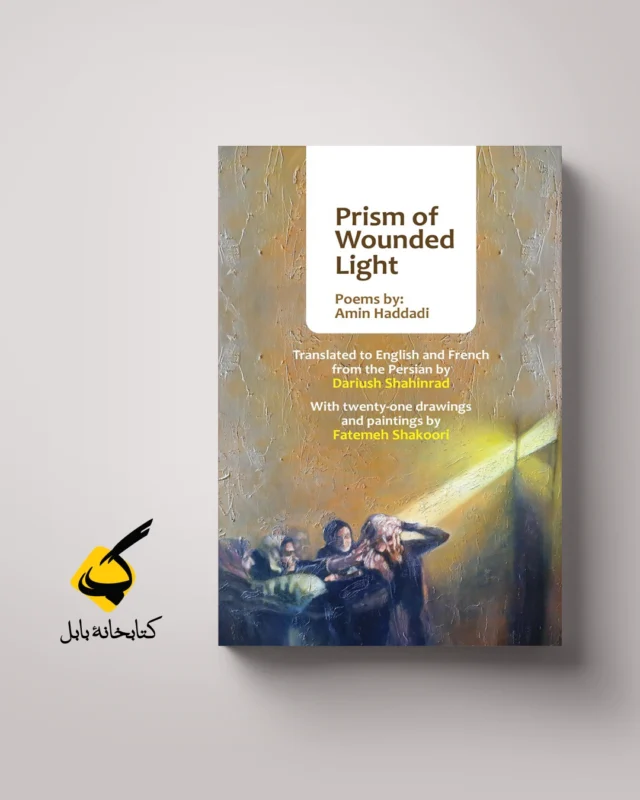

از منشورِ زخمِ نور

اشارهٔ شاعر¹

شاعر خبر دارد. چه میکردم این همه وقت؟ آیا همین حالا هم گزارش مینویسم؟ یادم رفته بود این را بگویم. ناشر از من خواسته برای کتاب مقدمه بنویسم. من که تمام عیشِ نوشتن را در همین فتح بابِ آشنایی با تو میبینم، معلوم است که خیلی قبلتر از این حرفها برایت نوشته بودم. «خبر» داده بودم. باور کن نمیخواستم گزارشگرِ شب باشم، آن هم حالا که زیر بمباران داشتم، خبر میشدم. خبر میپراکَنَد و شعر گرد میآورد: خبر همه را پراکنده است عزیز من. پس چطور شعر میخواهد «همه» را جمع کند. کلامِ پراکنده و «کلمه» را جمع کند. خبر کوتاه بود: تهران را زدند! چه میکردم این همه وقت؟ شاعر خبر دارد. پس نوشتهی قبلی را دور میاندازم.

گزارشِ کار بیهوده است: «آن» اینترنت را قطع میکند و «این» هشدار تخلیه میدهد و «او» گزارشِ کشتار میدهد. میبینی تمامِ ضمایر به هیچ اشاره میکنند. در شب سوم جنگ، در برهوتِ بلواری زیبا و هولناک در تهران شنیدم که فرشتهای شعلهور میگفت: شاعر باید که راز بداند. راستی چه کسی از ضمیرِ «تو» میگوید؟

میدانم که دربارهی هنرِ اکفراسیس میتوانی حرفها بزنی و تعریفهای بسیار ارائه کنی اما شاعر خبر میدهد. آخر در هنگامهی «هشدار تخلیه» مجالِ حرف نیست. فرشتگانِ «منشور زخم نور» افشا میکنند. شاعر راز میداند؛ و فارسی راز است. فعلِ «نگاشتن» در فارسی یعنی اکفراسیس. شاعر مینگارد. شاعری اینجا نگاشتن است. یکجور مینیاتورخوانی است: او که تمثال میخواند، دارد مینگارد. اکفراسیس یا همان اندیشیدن بهمدد تصویر و تصویر را نگاشتن؛ در کار من، مثل زخم زدن است یا چیزی را داغ کردن آن هم با کلمه. اما چرا طرح زدن با شعر؟ چرا طراحی و نقاشی؟ در کورانِ آن جنبشِ عظیم، دو نیرو، دو احساسِ شدید در خیالِ من بیداد میکرد؛ بیم و امید: شجاعتِ ساختن و سوگِ سوختن. در زایش و سوگ بهرغمِ تضاد، یک نیروی مشترک، جریان دارد: میل به برونافکندن، میل به چیزی از تنِ خود کَندن. نه نمایشِ نیستی و «یادبود» که گذشتهنگر است بلکه به غیاب و فقدان تنبخشیدن و «یادآر!» که رو به اکنون دارد.

کتابی که میخوانی حاصلِ نیروی سوگِ آفرینشگرانه است. تابلوها و طرحها زبان مرا باز کردند تا از تمثالِ باستانی و مخدوش قدیسانِ امروز، از فرشتگانِ مطرود و زخمِ نور بنویسم. شبی در اسفند ۱۴۰۱ در باغِ کوچک گالریِ خلوت در تهران از دهلیزِ سوگ گذشتم و حالا در هراس موشکبارانِ جنگ (۱۴۰۴) دارم به این کتیبهی بیم و امید نگاه میکنم. به شعلهی این شمع.

چقدر برهنه است شعلهی شمع! میبینی؟ بگذار آنچه در دل دارم با تو فاش بگویم: در تمامی شعرهای این کتاب، خیالِ برهنگیِ شعلهی یک شمع زبانه میکشد. سرچشمهی روشنایی یک زخمِ تاریخی که اکنون همچو منشوری پیش رویت، همچو آینهای برابر معشوق، چهرهی مرا گرم میکند. میدانم ممکن است شاعر در بند کشته شود یا به اشارتِ بمبارانی شبانه و نابهنگام بمیرد اما «شعر» شاهد میماند. وطن، این شمعِ برهنه، این سروِ شعلهور، شاهدِ کُشتگانِ خویش میماند.

ناگفته نماند که در آثارِ دیگرم، همواره «تنها» بودهام اما این کتاب ماحصلِ شعری جمعی است. شاید آنچه میخوانی از سرِ ناممکنی برگردان و ایدهی ترجمهناپذیریِ شعر پریده باشد. دیگر حرف بر سر ترجمه نیست که «منشور» است. شعرها ترجمه نشدهاند بلکه دمبهدم به بیانهای دیگر سروده میشوند. این است که هر کدام یک چیزند اما با زبانهای دیگر گاه به تصویر درمیآیند و گاه با خوانندگانِ سه زبانِ شعرباره [فارسی، انگلیسی، فرانسه] سخن میگویند. با این همه همیشه چیزی این وسط ناگفته میماند. نوری منتشرناشدنی؛ رازِ «منشور» در این است:

هرچند در صناعتِ نقش و علوم شعر

جز مر تو را روا نبود سرفراشتن

اوصافِ خویشتن نتوانی به شعر گفت

تمثالِ خویشتن نتوانی نگاشتن«کسایی مروزی»

امین حدادی

تهران/ تابستانِ ۱۴۰۴

خرید کتاب از آمازون:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1997503093

The Poet’s Note

The poet knows the news. What was I doing all this time? Am I still writing the report even now? I had forgotten to say this: the publisher asked me to write a preface for the book. But I, who find all the pleasure of writing in this very opening encounter with you, of course, I had written to you long before this request. I had reported it. Believe me, I never intended to be a reporter of the night—not now, when I was becoming the news under bombardment. News disperses; poetry gathers. But news has scattered everyone, my dear. So how can poetry hope to gather “everyone” again? To gather dispersed speech and the word itself? The news was brief: Tehran was bombed! What was I doing all this time? The poet knows the news. So I throw away the earlier draft.

Reporting is futile: “That one” cuts the internet. “This one” gives evacuation warnings. And “they” report the massacre. See? All the pronouns point to nothing. On the third night of war, in the desolate beauty and horror of a boulevard in Tehran, I heard a burning angel say: The poet must know the secret. But who even speaks from the pronoun “you”?

I know you can speak volumes about the art of ekphrasis and offer countless definitions—but the poet brings the news. After all, in the midst of an “evacuation warning,” there is no time for theory. The angels of the Prism of Wounded Light reveal. The poet knows the secret. And Persian itself is a secret. The verb “neveshtan” (to write) in Persian means ekphrasis. The poet writes. Poetry here is writing—a kind of reading of miniatures: one who reads the icon is writing. Ekphrasis—or thinking with images and rendering them in words—in my work, it’s like making a wound. Or branding something—with language. But why etch with poetry? Why draw or paint? In the heart of that great social uprising, two forces—two intense emotions—raged within my imagination: Fear and Hope—the courage to create, the sorrow of burning. In both birth and mourning, despite their contrast, there flows a shared force: a desire to cast out, to tear something from one’s own body. Not a display of absence or a nostalgic “memorial,” but an embodiment of absence—a “reminder!” which looks toward the now.

The book you are reading is the result of a creative mourning-force. The paintings and sketches opened my mouth, to speak of ancient and scarred icons of today’s saints, of fallen angels, and the wounded light. One night in Esfand 1401 (March 2023), in the quiet garden of a small Tehran gallery, I passed through a corridor of mourning. Now, in the terror of wartime missile strikes (1404 / 2025), I gaze upon this tablet of fear and hope—this candle’s flame. How naked the flame is! Do you see? Let me tell you frankly what I hold in my heart: in all the poems in this book, the image of a naked candle flame flares in my mind—the source of its light: a historical wound, now like a prism before your eyes, like a mirror before the beloved, warming my face. I know the poet may be killed in captivity, like Baktash, or might die from the impact of a sudden, midnight bombardment. But poetry remains witness. The homeland—this naked candle, this burning cypress—remains witness to its slain.

Let it not go unspoken: in my other works, I’ve always been “alone.” But this book is the product of collective poetry. What you read may arise from the impossibility of translation—the very idea of the untranslatable nature of poetry. This is no longer a question of translation—but of a prism. The poems have not been translated, rather, they are being composed, moment by moment, in other forms. Thus, each is a thing of its own—yet in other languages, sometimes they take visual form, sometimes they speak to readers in three tongues of poetry: Persian, English, and French. Still, something always remains unsaid in between—a light that cannot be published. The secret of the prism is this:

Even if in art and poetry’s craft

None but you may dare rise in pride,

Your own virtues, you cannot say in verse—

Your own image, you cannot draw.

— Kasa’i Marvazi

Amin Hadadi

Tehran, Summer 2025

۱. این متن، مقدمهی فارسی و انگلیسی مجموعه شعر «منشورِ زخمِ نور» (Prism of Wounded Light) اثر امین حدادی (اکفراسیس) است که در ۵ سپتامبر ۲۰۲۵ توسط انتشارات آسمانا در تورنتو، کانادا منتشر شد؛ بیستویک شعر سهزبانه (فارسی، انگلیسی و فرانسوی) با ترجمهی داریوش شاهینراد، به همراه بیستویک نقاشی و طراحی از فاطمه شکوری.

Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1997503093