ادای احترام به ویلکی کالینز

یک مرور جامع بر نُه رمان معمایی

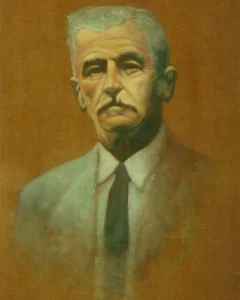

تی اس الیوت

معمای دآربلی ــ اثر آر. آستین فریمن

گامهایی که متوقف شدند ــ اثر ای. فیلدینگ

خانهی گناه ــ اثر آلن آپوارد

الماس در سُم ــ اثر تریل استیونسون

طلسم دنجرفیلد ــ اثر جی. جی. کانینگتن

ناپدیدشدنهای اسرارآمیز ــ اثر جی. مکلئود وینسور

گامها در شب ــ اثر سی. فریزر-سیمسون

معمای پارک اسقف ــ اثر دونالد دایک

پروانهی مسینگهام ــ اثر جی. اس. فلچر

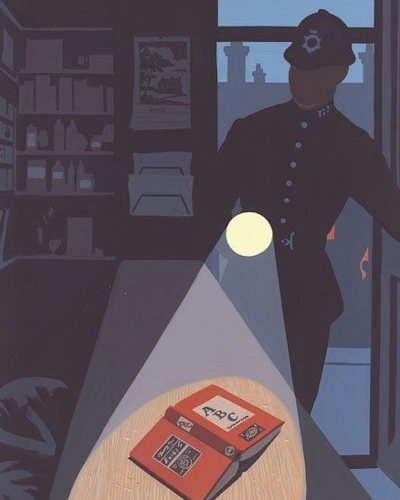

در یکدو سال اخیر، حجم تولید داستانهای کارآگاهی بهناگاه بالا گرفته، بهطوری که گمان میکنم ــ و این گمان بیدلیل نیست ــ چنین داستانهایی رونق یافته و تقاضا رو به فزونی گذاشته است؛ وگرنه چهگونه ممکن بود تقریباً در فهرست هر ناشر، یکیدو تا از این «تریلر»های مهیج پیدا شود؟ (گمانهزنی دربارهی علت فزونی این تقاضا میتواند سرگرمکننده باشد، ولی نتیجهاش هرچه باشد، سندی قطعی به دست نمیدهد). آنچه اما میتوان نشان داد، و خود فینفسه جالب هم هست، این است که همین افزایش تقاضا و رقابت، گونهای تازهتر ــ و بهگمانِ من برتر ــ از داستان کارآگاهی پدید آورده؛ آنقدر که میتوان برخی قواعد کلی برای فنون اینگونه داستانها معین کرد؛ و نیز اینکه، هرچه داستان کارآگاهی وفادار به «قواعد بازی» باشد، همانقدر هم به شیوهی عملی ویلکی کالینز نزدیک میشود. چراکه کتاب بزرگِ «سنگ ماه» (که بذر داستان کارآگاهی انگلیسی را کاشت) مادر همهی قوانین این بازی است، و هر داستان کارآگاهی، تا آنجا که «خوب» باشد، قوانین استخراجشده از همین کتاب را رعایت میکند. نمونهی اصیل داستان کارآگاهی انگلیسی از نفوذ «پو» برکنار مانده؛ خود شرلوک هلمز ــ با همهی خیل خلف معنویاش ــ در پارهای نکاتِ مهم، یک استثناست. اصطلاح «نمونهی اصیل انگلیسی» را هم از این رو به کار میبرم که داستان هر سرزمین، عطر و رنگ و لهجهی خاص خود را دارد؛ به همین قیاس جالب است که نشان دهیم قصههای جنایی فرانسوی ــ خاصه آرسن لوپن و جوزف رولتاویل ــ همانطور که داستانهای انگلیسی به «سنگ ماه» میرسند، به «کنت مونتکریستو» دوما میرسند؛ اما این رهرو گفتوگو را از مقصود ما دور میکند.

داستان کارآگاهی را نمیتوان همچون انواع دیگر داستان تحلیل کرد: منتقد نباید طرح داستان را لو بدهد (وگرنه لذت خواننده تباه میشود). از این رو است که این مجموعهی کوچک، اما بهگمان من نمایندهی محصول فصل جاری، را بر پایهی سلسلهمراتبی که از حیث ارزششان میشناسم، چیدهام. «پروانهی مسینگهام» را باید «خارج از رقابت» گذاشت؛ چراکه، در عمل، چیزی نبود جز مجموعهای از داستانهای کوتاه بیارتباط با هم از نوع کارآگاهی (که نه آنقدر ارزش داشتند که بازچاپ شوند و نه از جهت قوام فنی درخور تأمل بودند)، هرچند همین اثر، نشان میدهد که رمانهای بلندتر آقای فلچر لابد محکمترند. دو کتاب پیش از آن («گامها در شب» و «معمای پارک اسقف») اساساً کارآگاهی نیستند، چرا که فاقد کارآگاهاند؛ و از این بابت، از نظر فنی، ارزش اندکی دارند. باقی آثار، هر چند بیبهره از حسن نیستند، اما همه، بهگونهای که کالینز هرگز نمیکند، یک یا چند قاعده از قواعد روشن بازی را نقض کردهاند.

نمیدانم چند قاعده را میتوان دقیقاً صورتبندی کرد، اما این چند اصلِ پیش رو، از دل همین آثار و نیز موارد مشابه تازهتر به دست آمده و «ادعای جامع بودن» ندارد. هر کدام از این کتابها لاجرم مرتکب یکی از این خطاها شدهاند، البته شدت و ضعف و گاه بخشودنیبودنشان تفاوت میکند:

۱. نباید داستان بر مکر و تغییر چهرههای پیچیده و نامحتمل بنا شود. این را از شخصیتی دلنشین چون هلمز میپذیریم، همانگونه که از لوپنِ لودهتر؛ اما در اصل، این کار، حقهبازی است. تغییر چهره باید گهگاه و حاشیهای باشد؛ کالینز در این مورد بیعیب است. زندگیهای دوگانهی پرآرایش هم افراط همین عیباند: لوپنِ ملبس به هیئت رئیس پلیس پاریس، که چهار سال تمام واقعاً هم همان رئیس بود، محظوظکننده است، اما در مجموع نارواست. اگر «گامهایی که متوقف شدند» این حربه را به کار نمیبست، بهترین اثر فهرست میبود.

۲. شخصیت و انگیزهی جنایتکار باید عادی باشد. در داستان کارآگاهی ایدهآل، خواننده باید حس کند شانسی «منصفانه» برای حل معما دارد؛ مجرمِ بیش از حد غیرعادی، عنصری غیرعقلانی را وارد متن میکند که آزاردهنده است. جنایت بیعلت، یا بیعلت طبیعی، همان حس فریبخوردگی را القا میکند. اگر این عیب نبود، داستانی دیگر در فهرست من، جایش بالاتر از «معمای دآربلی» میبود. هیچ سرقتی، مثلاً، نباید نتیجهی «کلپتومانیا» باشد (ولو که چنین بیماریای حقیقی باشد).

۳. داستان نباید بر پدیدههای ماوراءالطبیعی یا، که در اصل همان باشد، بر کشفیات غریب و بیپایهی دانشمندان منزوی تکیه کند. این نیز افزودن عنصر غیرعقلانی است: اشباح، تأثیرات مرموز، عناصر ناشناخته با خواص هولناک («انهدام اتم» لابد تا سالها در داستانهای بد، رونق خواهد داشت) همه در یک دستهاند. نویسندگان این قبیل شعبدهها شاید پشتگرم به نام اچ.جی. ولز باشند، ولی ولز درست به این خاطر در داستان علمیـتخیلی پیروز است که در محدودهی ژانر خود میماند. واقعیت او روی بستری دیگر است. در کارآگاهی برای این قماش، جایی نیست. دو اثر فهرست ما این خطا را مرتکب شدهاند.

۴. ابزار و مکانیزمهای غریب و پرآرایش، بیرون از متن اصلی معما، زایدند. نویسندگان کارآگاهیِ سختگیر و کلاسیک اینها را نمیپسندند. در بعضی داستانهای هلمز، این «لوازم صحنه» بیش از حد پررنگ میشوند. علاقهمندان به گنج پنهان، رمز و کد، علامت و آیین، نباید دلگرم شوند. البته باید فرق گذاشت: در «حشرهی طلاییِ» پو، رمز خوب است، چون به خواننده تمرین فکری مشروع میدهد؛ اما خود حشره و جمجمه تزیینات کودکانهاند. در «سنگ ماه»، «ماجرای هندی» ــ با اینکه تقلیدهای قلابی هندیمآب بسیاری گنجانده ــ در محدودهی عقلانیت است؛ هندیهای کالینز، انسانهایی هوشمند و با انگیزههای موجهاند.

۵. کارآگاه باید هوشمند، اما نه مافوقبشر باشد. خواننده باید بتواند استدلالهای او را دنبال کند و تقریباً، ولی نه کاملاً، به همان نتایج برسد. شاید بیشترین پیشرفت داستان امروز ــ که در واقع بازگشت به گروهبان کاف است ــ در همین جایگاه کارآگاه باشد. شمار کارآگاهان حرفهای، مجرب اما خطاپذیر، در داستانهای تازه چشمگیر است؛ پلیس جنایی (CID) احیا شده و کارآگاه آماتور دیگر همهکاره نیست. در کنار بازرس CID، نمونهی موفق دیگر، دانشمند پزشک است که کارش او را به جرم میکشاند. دکتر ثورندایکِ فریمن و دکتر تارلتونِ آپوارد هم حرفهایهای بیادعا هستند؛ شخصیت دارند، ولی زوائد نمایشی ندارند. یکی از درخشانترین لحظات در کل داستان کارآگاهی، شیوهی معرفی گروهبان کاف در «سنگ ماه» است (در روایت پیشخدمت، بترج). ظاهرش بیجاذبه و کسلکننده است، تا اینکه ناگهان، در حین صحبت با باغبان دربارهی گل رز، میگوید: «آها، زنی دارد میآید. آیا ممکن است لیدی ورایندر باشد؟» بترج و باغبان انتظار آمدن لیدی ورایندر را داشتند، آن هم از همان سمت؛ کاف نه. از همانجا بترج گمانش نسبت به کاف بهتر میشود. این نه مافوقانسان بودن کاف، که ذهن و حواس تربیتشدهی اوست.

از میان جوانترهای این رسته، بازرس گیلمور در «ناپدیدشدنهای اسرارآمیز» نویدبخش است: تندمزاجی اش اتفاقاً بهجاست و خصایل و محدودیتهایش چنان واقعنماست که اگر نویسنده از شعبدهی علمیاش (خطای شمارهی ۳) دست بردارد، آیندهای درخشان دارد. از همهی نامهای فهرست، «معمای دآربلی» کاملترین از حیث فرم است؛ دومی، بهخاطرِ طرح پخته، شایان توجه است و فقط در اواخر طرح، نامحتمل میشود؛ سومی نیز کاریست درخور ستایش. مابقی، زیر سایه این سه میمانند.

New Criterion

ژانویهی ۱۹۲۷