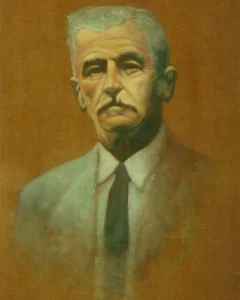

یک تصادف ساده: امید به چه کسی؟

امید به چه کسی؟

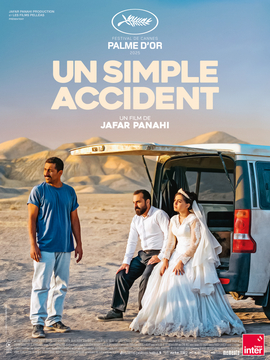

[نقد فیلم آخر جعفر پناهی: یک تصادف ساده]

جعفر پناهی با فیلم آخرش دوباره نشان داد که سینمایش با دکوپاژهای سردستی، دیالوگهای گلدرشت، بازیهای بد، تیپسازیهای باسمهای، و مهمتر از همه، عدم پایبندی به کنشها و رخدادهای واقعی در سینمایی که قرار است واقعگرا باشد، هرگز به هنر بزرگ سینما تعلق ندارد.

پیشتر در متنی نوشتم که او ادعایی هم بابت خلق سینمای بزرگ ندارد. این بیادعایی نه در گفتهها یا روحیات او، بلکه در فرم سینمای او مشهود اوست (مثلاً برخلاف سینمای رسولاف و قبادی که همواره با حرکت دوربینهای پیچیده و تقطیعهای درونی در قاب در پی نوعی زیباشناسی والایشیافته هستند). سینما برای پناهی صرفاً محلی برای گفتگو در بارهی شیوهها، پیآیندها، و چگونگی مبارزه با حکومت است. اما هرچقدر او (چه از سر ناتوانی چه عامدانه) در فرم سینمایی بیادعاست، در آنچیزی که میتوان آن را تجویز اخلاقیات مبارزه نامید، تماماً مدعیست.

عجالتاً بیایید از سینمای بزرگ صرفنظر کنیم و او را در چارچوب همین ادعایش بررسیم. اما در این صورت نیز فیلم آخر او، یک تصادف ساده، تریبونی تماماً ارتجاعی و ناامیدکنندهست که از یکسو آگاهانه در پی تسویه حساب با آدمهای نامحبوبش در اپوزیسیون، و احتمالاً ناآگاهانه در پی همدلی روانشناختی با آدمهای حکومت است.

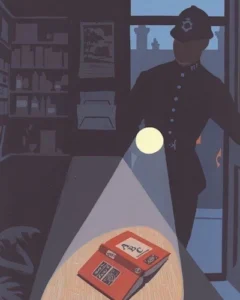

حمید و گلی ظاهراً همان کلهخرهای توییتری هستند که یک لحظه فحش از دهانشان نمیفتد و در ابتدا خشمی افسارگسیخته دارند، اما وسط ماجرا جا میزنند و مبارزه را به بهانههایی شخصی نیمهکاره رها میکنند. آقای اقبال نیز نمایندهی همان بازجوهاییست که در اثر عقدههای کودکی (خدای من، نه!) و تامین هزینههای زندگی برای خانوادههای نرمالشان، مترسکهای ابتذال شرّ شدهاند و دست به جنایت میزنند. اما دو نفری که تا پایان میمانند (از قضا یکیشان کارگر است و دیگری عکاس_خبرنگاری از طبقهی متوسط) همان کسانی هستند که بار سنگین اخلاق مبارزه را به دوش میکشند. آدمهایی که در زندان آقای اقبال شکنجه شدهاند و زندگی اجتماعیشان تباه شده است، اما آخر سر بخشش بزرگوارانه را پاس میدارند و با یک «گوه خوردم» از دهان آقای بازجو ارضا میشوند و میروند پی زندگی انسانی (بسیار انسانی)شان. اما در صحنهی پایانی آقای بازجو که هم به دست آنها شکنجه شده، و هم لطف آنها به زن باردار و دختر کوچکش را دیده، از راه میرسد. فیلم تمام میشود و این پرسش باقی میماند که آقای بازجو برای انتقام آمده است یا توبه و تشکر (تب تمامنشدنی سینمای اصغر فرهادی که هنوز دل جشنوارهها را میبرد) این پایان باز یعنی فیلمساز هنوز امیدوار است. اما امید به چه کسی؟

Hope in Whom?

[A Review of Jafar Panahi’s Latest Film: It Was Just an Accident]

Jafar Panahi’s newest film once again underscores that his cinema—marked by slapdash découpage, overwrought dialogue, subpar performances, clichéd archetypes, and above all, a flagrant disregard for authentic actions and events in what purports to be a realist mode—has no rightful place in the exalted realm of great cinematic art.

As I observed in an earlier essay, he lays no claim to forging grand cinema. This unassuming stance reveals itself not in his pronouncements or temperament, but in the very form of his filmmaking (unlike, for instance, the cinema of Mohammad Rasoulof and Bahman Ghobadi, which relentlessly pursues a sublime aesthetic through intricate camera movements and internal framing cuts). For Panahi, the medium serves merely as a platform for deliberating the strategies, repercussions, and practicalities of resistance against the regime. Yet, for all his modesty in formal execution (whether born of incapacity or intent), when it comes to what might be termed the prescriptive ethics of struggle, he asserts himself with utter conviction.

For the moment, let’s set aside the notion of grand cinema and evaluate him strictly within the bounds of his own professed aims. Even so, his latest film, A Simple Incident, emerges as a thoroughly reactionary and disheartening pulpit—one that deliberately settles scores with his disfavored figures in the opposition, while perhaps unwittingly fostering a psychological empathy for the regime’s operatives.

Hamid and Goli appear as stand-ins for those hotheaded Twitter trolls whose mouths never cease spewing invective, who erupt in unbridled fury at the outset, only to bail midway through, abandoning the fight under personal pretexts. Mr. Eqbal, meanwhile, embodies those interrogators who, scarred by childhood complexes (good God, really?) and driven to provide for their utterly ordinary families, have devolved into banal scarecrows of evil, committing atrocities. But the two who endure to the end (one, tellingly, a laborer; the other, a middle-class photographer-journalist) are the ones shouldering the weighty moral burden of resistance. These are individuals who’ve been tortured in Mr. Eqbal’s prisons, their social lives ruined, yet in the finale they extend a magnanimous forgiveness, content with a mere “I fucked up” from the interrogator’s lips before heading off to reclaim their profoundly human (oh-so-human) existences. But in the closing scene, Mr. Eqbal—who’s been tortured by them in turn and witnessed their kindness toward his pregnant wife and young daughter—reappears. The film ends, leaving us with the question: Has the interrogator returned for vengeance, or for repentance and gratitude (that undying Asghar Farhadi trope, still charming festival juries to this day)? This open ending signals that the filmmaker clings to hope. But hope in whom?